A review of mentoring programs added to the model programs guide by the national mentoring resource center: 2014 – 2021

Model/Population Review

Researchers

Timothy Brezina, David L. DuBois, Alyson Giordano, Aisha Griffith, Julia Pryce, and Kelly Stewart,

Download Full Report

Download PDFSummary

Background

A total of 47 mentoring programs were added to the Model Programs Guide by the NMRC between January 2014 and January 2022. Programs were rated Effective (n = 3; 6%), Promising (n = 27; 57%) or No Effects (n = 17; 37%). Upon completion of each program’s review, an informational profile was added to CrimeSolutions.gov and program insights were added to the NMRC website. Drawing on those documents, as well as program reviewers’ scoring instruments, this report provides an overview of the programs added and their evaluations as well as key themes from program insights.

Findings

Program and Evaluation Characteristics. Roughly half of the programs reviewed received the highest score from at least one reviewer in the degree to which their conceptual framework (59%) was supported by research, and the strength of their program theory (46%). About a third of programs (36%) included non-mentoring components, such as a curriculum delivered by non-mentor adults or mental health services.

Programs mostly took place in the U.S (n = 42; 87%), in urban and/or suburban areas (n = 31, 82%). About half took place in schools (n = 25, 53%) and the other half took place in other community settings (n = 22, 46%). About half of the programs used a one-to-one model of mentoring (n = 24, 51%), while others used either an exclusively group format (n = 8, 17%) or combined group/one-to-one format (n = 10; 21%). While most programs used adult mentors, 17% (n = 8) used peer mentors. Programs typically were delivered to both male and female youth, other than 3 programs that were girl-specific, and served diverse racial groups.

Studies constituting the evidence base for the mentoring programs reviewed were published between 2002 and 2021, and only 5 (11%) programs were evaluated across multiple studies. While 72% of programs (n = 34) had a randomized controlled trial in their evidence base, only about half of the programs (n = 24) had a study that was considered a high quality RCT (i.e., Randomized Controlled Trial) as defined by CrimeSolutions.

Program details (e.g., activities involved) were described thoroughly as judged by reviewers. There was some inconsistency, however, in the degree to which the data and information required to assess whether programs were implemented in alignment with their descriptions were collected as part of evaluations. When such information was available, most programs (74%, n = 29) were rated as having satisfactory adherence, meaning the core components or services were for the most part delivered as intended.

The majority of evaluations (n = 29; 62%) targeted at least one academic- or career-related outcome (e.g., failure or dropout risk), about half targeted a SEL- or mental health-related outcome (n = 25; 53%), and less than half (40%; n = 19%) had at least one justice-related outcome (e.g., arrests/offending).

Significance testing was used to see if programs rated Effective or Promising differed from those rated No Effects on selected program study characteristics. The most noteworthy finding is that programs rated Effective or Promising were less likely to have been evaluated in a high-quality RCT. Other characteristics, including conceptual framework, program theory, program components other than mentoring, program setting, mentoring format (i.e., one-to-one versus group and combined group/one-to-one), mentor age, mentee age, mentee gender, mentee race, number of studies per program, and type of outcomes evaluated (i.e., academic, mental health/SEL, justice related) were not associated with evidence ratings.

Thematic Analysis of Program Insights. Five broad themes were identified across the “Program Insights for Practitioners” documents:

- Ensuring Alignment Across Program Goals, Design, Implementation, and Evaluation

- Connections Between Mentoring Intervention and Mentees’ Home, Parents, and Larger Environment

- Engaging Others (i.e., peers, teachers, etc.) as a Web of Mentoring Support

- Tailoring Mentor Recruitment, Selection, Preparation, and Support to Effectively Serve Youth

- Optimizing the Role of Mentoring Within the Context of Programs with Multiple Components

Implications for Research and Practice

Findings highlight the importance of periodically analyzing trends and patterns in mentoring programs undergoing evaluation and the findings of such studies. Rather than point to a single template for program effectiveness, findings support the potential effectiveness of a variety of models and approaches. Our analysis also suggests areas in need of increased coverage, such as mentoring for rural youth and male-specific mentoring, a need for increased use of rigorous RCTs, and the importance of developing strong and deliberate program designs that are intentionally linked to program needs, resources, and desired behavioral outcomes.

Background

Since the inception of the National Mentoring Resource Center (NMRC) in 2014, its Research Board has reviewed youth mentoring programs for inclusion in the Model Programs Guide (MPG) of the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP). NMRC Research Board Chair David DuBois has served as the Senior Researcher overseeing these reviews, except in cases of conflict of interest, in which case reviews have been led by a Senior Researcher at Development Services Group, Inc. (DSG). Links to the profiles for mentoring programs are posted to the NMRC website. Each profile is accompanied by Program Insights, which are written by Michael Garringer, Director of Research and Evaluation for MENTOR.

This report starts with an overview of mentoring program reviews conducted between 2014 and 2021; continues with a synthesis of key themes from the Program Insights; and concludes by identifying “take aways” for practice and research.

Mentoring Programs Reviewed for Model Programs Guide

The MPG shares a database with CrimeSolutions.ojp.gov and uses the standardized CrimeSolutions review process to assign each reviewed program an evidence rating of Effective1, Promising2, or No Effects3, excepting those for which there is a finding of Inconclusive Evidence.4 A total of 47 mentoring programs were added to the MPG based on reviews led by the NMRC between January 2014 and January 2022. For more information about the CrimeSolutions review process and our approach to analysis for CrimeSolutions profile data, please refer to the Methods box below.

|

Methods A profile is prepared for each program that receives an evidence rating in CrimeSolutions, which includes coded program and study attributes such as demographics of the youth served and study design. Additional programs were reviewed by the NMRC but were ultimately not added because they were deemed to have insufficient research evidence to assign a rating (i.e., they received the Inconclusive Evidence designation referenced above). These latter programs were excluded from the present review based on lack of program profile information and Program Insights. Mentoring programs added to the MPG that predate the NMRC also were excluded due to their lack of Program Insights. CrimeSolutions profile information obtained from the CrimeSolutions.OJP.gov website served as the basis for this summary. Along with narrative text, this information includes structured codes pertaining to a wide range of characteristics of the programs and their evaluations. Several additional variables were also constructed from the available information. For instance, a program format variable was created from narrative program descriptions to differentiate between programs that used a group, one-to-one, combined, or other format. Data for three variables were obtained from reviewer scoring instruments: Program Description, Program Documentation, and Program Adherence. Descriptive statistics were generated, and chi-square analyses or Fisher’s Exact test was used to investigate whether program effectiveness rating varied in association with characteristics of programs and/or the associated studies constituting their evidence base. Due to the small number of programs rated as Effective these programs were combined with those rated as Promising for purposes of these analyses. Two implementation variables, Program Documentation and Program Aderence, were not included in significance testing because they are inherently related to the final program scores. |

A summary of the programs and evaluations, organized by evidence rating, can be found in Table 1a in the appendix. Three of the 47 programs (6%) were rated Effective, just over half (n=27; 57%) of programs were rated Promising, and about a third (n=17; 37%) received a rating of No Effects. The corresponding proportions of programs in CrimeSolutions as a whole (n = 652) programs at the time of the writing of this report) that have received these different ratings are as follows: Effective (14%), Promising (60%), and No Effects (27%).

The sections below describe program characteristics such as program components, setting, mentoring format, and characteristics of youth served including age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Next, we describe evaluation study characteristics including date of publication, study design, program implementation assessment, and program outcomes. Finally, we examine whether significant differences exist between programs rated Promising or Effective and those rated No Effects on any of the program and study characteristics.

-

References 1 An explanation of the CrimeSolutions Continuum of evidence can be found at https://crimesolutions.ojp.gov/about/crimesolutionsgov-evidence-continuum Programs rated Effective “have strong evidence to indicate they achieve criminal justice, juvenile justice, and victim services outcomes when implemented with fidelity.”

2 Programs rated Promising “have some evidence to indicate they achieve criminal justice, juvenile justice, and victim services outcomes. Included within the promising category are new, or emerging, programs for which there is some evidence of effectiveness.”

3 Programs rated No Effects “have strong evidence indicating that they had no effects or had harmful effects [on justice-related outcomes] when implemented with fidelity.”

4 Programs determined to have inconclusive evidence are those for which reviewers determined that the available evidence was inconclusive for a rating to be assigned. Reasons for this designation include Inadequate Design Quality (for example, small sample size, threats to internal validity, high attrition rates, etc.), Limited or Inconsistent Outcome Evidence (inconsistent or mixed results such that it is not possible to determine the overall impact of the program on justice-related outcomes), and Lacked Sufficient Info on Program Fidelity (sufficient information was not provided on fidelity or adherence to the program model such that it is not possible to determine if the program was delivered as designed).

Program Characteristics

Conceptual Framework and Program Theory

Reviewers rated the degree to which the conceptual framework of each program was supported by previous empirical research, such as formal evaluations or meta-analyses. Programs were scored on a scale from 0-3, where 0 = no support (i.e., no studies provide evidence in support of the program), 1 = low (i.e., one other study provides support for the program), 2 = medium support (2-4 other studies show evidence in favor of the program, and 3 = high support (i.e., 5 or more, or 1 one meta-analysis shows evidence in favor of the program). Of the 39 programs for which a rating of the conceptual framework was available, 59 percent (n = 23) received the highest score (i.e., a 3) from one or both reviewers.

Reviewers also rated the extent to which programs had a well-developed program theory on a scale of 0 – 3, with 0 = no information or the program theory is invalid, 1 = very little information, but the theory may be conceptually sound, 2 = program theory is adequately described and appears conceptually sound, and 3 = program theory is both well-articulated and conceptually sound. Of the 39 programs for which program theory data was available, 46 percent received the highest score (i.e., a 3) from one or both reviewers.

Components

All of the 47 programs included youth mentoring as a significant program component. Seventeen programs (36%) also included other program components, such as a curriculum delivered by non-mentor adults (e.g., Better Futures – Effective; Coaching for Communities – Promising; iMentor College Ready Program – No Effects) or mental health services (e.g., SAM Program for Adolescent Girls – Promising).

Setting

Setting characterizes the countries where the reviewed mentoring programs were implemented, geographic location (i.e., urban, suburban, rural), site location (i.e., school, community, home, college campus, work-place). The overwhelming majority of the programs were implemented and evaluated in the U.S (n = 42; 87%). Other program locations included the United Kingdom (i.e., Chance UK – No Effects; Coaching for Communities – Promising), Canada (i.e., Pathways to Education – Promising), Germany (i.e., Baloo and You – Promising), Mexico (i.e., Peraj Mentoring Program – Promising) and Rwanda (i.e., Mentoring Program for Youth-Headed Households – Promising).

For the 38 programs for which more specific geographic setting data are available, a vast majority took place in urban and/or suburban areas (n = 31, 82%). Only 7 programs (18%) took place in rural areas, with three (8%) of these programs taking place in rural communities alone. Rural mentoring programs tended to focus on specific, sometimes high need, populations of youth, such as youth in foster care (My Life – No Effects), youth heads of households due to parental loss (Mentoring Program for Youth-Headed Households in Rwanda – Promising), youth with emotional problems (Cognitive-Behavioral Intervention for Children with Emotional and Behavioral Disturbances, Regular and Group versions – both Promising), and youth with ADHD (Challenging Horizons, Mentoring and After-School versions – both No Effects). One rurally-located program, Sources of Strength (Promising), targeted youth universally as part of a school-wide suicide prevention intervention.

Mentoring programs took place across multiple types of settings. The most commonly reported setting was schools (n = 25, 53%). These programs were typically confined to the school setting only, though three of them extended outside of school for either home visits (i.e., Check and Connect Plus Truancy Board – Promising) or college prep activities (i.e., Bottom Line and Pathways to Education – both Promising). Remaining programs (n = 22, 46%) took place entirely in community settings. Some of these were group programs taking place in specific locations, such as Arches Transformative Mentoring (No Effects), but more often mentoring was designed to take place in varied community settings as determined by the youth and mentor. There were also several instances in which at least some of the mentoring took place in mentees’ homes (n = 6, 13%). Two of these programs took place exclusively in youths’ homes; they were targeted towards youth who were heads of their households (Mentoring Program for Youth-Headed Households in Rwanda – Promising) or soon to be emancipated youth in foster care (Early Start to Emancipation Preparation – Tutoring Program – No Effects). Two programs took place on college campuses. Bottom Line (Promising) was promoted in high schools and by other community agencies and took place primarily on college campuses. The Peraj Mentoring program (Promising) also took place primarily on campuses, but mentors were encouraged to organize off-campus group activities. One program, One Summer Plus Jobs Only (No Effects), provided workplace-based mentoring (note: a second version of the program that included an additional weekly social-emotional learning [SEL] component, One Summer Plus Jobs + SEL, was also reviewed for CrimeSolutions but not assigned a rating due to inconclusive evidence).

Mentoring Format

Mentoring format includes one-on-one or group mentoring and delivery in-person or online. About half of the programs used an exclusively one-to-one model of mentoring (n = 24, 51%), while others used either an exclusively group format (n = 8, 17%) or combined group/one-to-one format (n = 10; 21%). Two programs (4.3%) did not fit into either category; rather, they used a model in which youth identified as “influential peers” were trained to deliver prevention messages to other students in their schools. This included a Stop Smoking in Schools Trial (ASSIST) Program (No Effects) for high school students and Sources of Strength (Promising), the previously-referenced suicide prevention program for middle schoolers.

For the most part, mentoring took place in-person. Three programs (6%) either included an e-mentoring component or took place entirely online. In two of these programs, iMentor’s College Ready Program (No Effects) and the Helping One Student to Succeed (HOSTS) Program (Promising), e-mentoring was used to supplement an in-person classroom curriculum delivered to the youth. The third program, an E-mentoring Program for Secondary Students with Learning Disabilities (Promising), consisted primarily of e-mentoring, though the program ended with in-person college visits and lunch with the mentor.

Mentor Age

Mentors in the programs included adults and youth of various ages. While program mentors were usually adults, eight programs (17%) connected youth with peers close to their age. Three programs, Better Futures (Effective), SOURCE (Student Outreach for College Enrollment) Program (No Effects), and the E-Mentoring Program for Secondary Students with Learning Disabilities (Promising),5 paired college students with upper-class high school students to aid with their transition to college. The Cross-Age Peer Mentoring Program (Promising) similarly paired high school students with middle-schoolers to improve their connectedness to school and other academic outcomes. For programs in which the peer mentor was a high school or middle school student, skill development for mentors was an aim as well, through both training and supervision by program staff (i.e., ASSIST – No Effects) or school staff (i.e., Peer Group Connections – No Effects; Sources of Strength – Promising) and through mentor-mentee interactions. Two programs, Better Futures (Effective) and My Life Mentoring (No Effects), provided near-peer mentoring delivered by youth with similar foster care backgrounds to mentees in addition to other program services.

Mentee Characteristics

Youth served in the programs reviewed varied in age range, gender, and race and ethnicity.

Age. Information on the minimum and maximum age of youth served by the program was available for 41 of the 47 programs. Programs served youth as young as 5 years old. Program youth were typically within an age range of 5 years (M = 4.68 years, SD = 3.18). Five (12%) programs served a wider age range of youth; three of those programs (7%) served children through teenagers: Great Life Mentoring (Effective), Eye to Eye (Promising), and Check and Connect (No Effects). Other programs served exclusively teens at the ages 13 and older (n = 20; 49%), pre-teens at the ages of 10 to14 (n = 7; 17%), or children at the ages of 8 to 12 (n = 9; 22%).

Four programs (10%) served youth who were 20 years or older in addition to youth under 18, and they all targeted youth for specific needs. For example, the Mentoring Program for Youth-Headed Households in Rwanda (Promising) targeted youth who were forced into family leadership roles as a result of parental loss. The Arches Transformative Mentoring Program (No Effects) targeted youth on probation. One Summer Plus – Jobs Only (No Effects) targeted youth in high-violence neighborhoods seeking jobs. Finally, Promoter Pathways (No Effects) targeted youth with multiple risk factors as they transitioned to college.

Gender. Nearly all programs served both male and female mentees (n = 44; 94%). Only three programs (6%), each rated Promising, were girl-specific programs that targeted delinquency and substance abuse (i.e., Keep Safe, the SAM Program for Adolescent Girls) or parenting and mental health (i.e., the Home-Visiting Program for Adolescent Mothers). No programs focused on male-specific mentoring. While such programs have been reviewed (e.g., Becoming a Man), they were not assigned an evidence rating (i.e., Inconclusive Evidence) and thus not added to the MPG.

Race and ethnicity. Information about the racial identity of youth served by the program was available for 42 of the 47 programs. Racial groups were well represented across the programs. Thirty seven (88%) served Hispanic youth, 36 (86%) served Black youth, 33 (79%) served White youth, 15 (36%) served Asian/Pacific Islanders, and eight (19%) served American Indian/Alaska Native youth. Programs tended to serve diverse groups of youth, with 4 (n = 12) being the most common number of racial groups reported.

One program served a culturally-specific ethnic group. Gear Up! Mentoring in Mathematics (Promising) served an exclusively Hispanic, high-poverty high school. In this program, youth were matched with Hispanic mentors who were from the same neighborhood and could act as credible messengers.

-

Reference 5 College to high school mentoring programs were considered peer mentoring for this review only if the high school students were primarily of upper-class student status.

Evaluation Study Characteristics

Publication Date

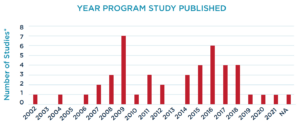

Studies constituting the evidence base for the mentoring programs reviewed were published between 2002 and 2021 (Figure 1). While there has been an increase in the number of evidence-based evaluations over time, disruptions due to Covid-19 and new guidelines for reviewable outcomes may have contributed to having fewer recent mentoring evaluations in the database.

Figure 1.

*For programs with more than one study in their evidence base, only the most recent study was counted.

Number of Studies

Ten programs (26%) have two studies in their evidence base, though only five of the ten (11%) were evaluated across multiple independent samples. The latter programs include two programs rated Promising (Bottom Line and Cross-Age Peer Mentoring Program), and three programs rated No Effects (Check and Connect, Citizen Schools Extended Learning Time. Model, and Project Arrive).

Research Design

While 72 percent of programs (n = 34) had a randomized controlled trial in their evidence base, just over half of the programs (n = 24) had a study that was considered a high quality RCT as defined by CrimeSolutions.6

Program Fidelity

To assess whether a program has been implemented with fidelity to its design, it is necessary to have a clear and detailed description of the program and its components. An item on the CrimeSolutions review instrument, which was available for 39 of the 48 programs, assesses program description on a 0 to 3 scale where 0 = none, 1 = some, 2 = most, and 3 = all, to indicate how many of the following indicators were included in the program description: logic of the program, key program components, the frequency and duration of the program activities, population targeted, program goals (i.e., targeted behavior(s)), and program setting. This information was available for a large majority of the 39 programs, with 87 percent (n = 34) receiving the highest rating for the relevant item by one or both reviewers. It also is necessary to systematically collect information about the extent to which the program is implemented or delivered in alignment with its description. An item on the CrimeSolutions review instrument asks about this, with response options of 0 to 3: 0 = no implementation data was provided at all, 1 = implementation data were collected non-systemically, 2 = qualitative data (e.g., focus groups, interviews) were collected systematically, and 3 = quantitative data (e.g., dosage, adherence to program manual) were collected systematically. Reviewer ratings on this item indicate some inconsistency in collection of implementation data. Specifically, whereas nearly two thirds (n = 25; 64%) of programs received the highest score on this item by at least one reviewer, substantial minorities of programs were found by both reviewers to have only collected qualitative date (i.e., a rating of 2; n = 2; 5%) or to have collected data non-systematically or not at all (i.e., rated a one or a zero by both reviewers; n = 4; 10%). Importantly, a further item asks reviewers to evaluate whether the core components or services were delivered as intended; 74% (n = 29) of programs were rated by both reviewers as having satisfactory program adherence (i.e., research indicated the core components or services were delivered as intended).

Outcomes Evaluated

Measures of program outcomes were collected in studies anywhere from one to 60 months after baseline (M = 19.29, SD = 13.84). The majority of programs (62%) targeted at least one academic- or career-related outcome (e.g., failure or dropout risk), slightly more than half targeted a SEL- or mental health-related outcome (53%), and just under half (40%) had at least one justice-related outcome (e.g., arrests/offending). Table 1 shows a more detailed summary of study outcomes.

Table 1. Types of Program Outcomes Evaluated*

Programs that included at least 1 related outcome:

Academic/Career (N = 29)

- Graduation (n = 11)

- Failure or dropout risk (n = 3)

- Career/employment outcomes (n = 5)

- College (n = 6)

- Attendance (n = 7)

- GPA (n = 11)

SEL/Mental health (N = 25)

- SEL (n = 16)

- Mental health (n = 14)

Justice-related (N = 19)

- Arrests/offending (n = 8)

- School discipline (n = 6)

- Drinking, smoking, or drugs (n = 7)

*Numbers in the table indicate how many of the evaluated programs included a given type of outcome.

Association of Program and Study Characteristics with Program Effectiveness Ratings

As noted previously, analyses were conducted to test for possible differences in the characteristics and evaluations of programs that were rated Promising or Effective (n = 30) and those rated No Effects (n = 17). Of the program characteristics investigated, only the degree to which the program was supported by prior research is significantly associated with program rating, such that programs that received the highest prior research score (i.e., a 3) from one or both reviewers are more likely to be rated No Effects (52%) compared to programs with lower prior research scores (12%). No statistically significant differences emerged between the two groups of programs in the other program characteristics measured, including conceptual framework, program theory, program components other than mentoring, setting, mentoring format (i.e., one-to-one, group, combined group/one-to-one), mentor age, mentee age, mentee gender, and mentee race and ethnicity.

Certain study characteristics also exhibit statistically significant associations with program effectiveness rating. In particular, programs evaluated using high-quality RCTs are more likely to be rated No Effects (76%) compared to those without a high-quality RCT (17%) as are programs with more recent studies in their evidence base (i.e., studies published since 2014; 52%) compared to programs with studies published prior to 2014 (19%). 7 No statistically significant differences emerged between the two groups of programs in the other study characteristics measured, including number of studies per program, research design, and type of outcomes evaluated.

-

References 6 As defined by CrimeSolutions, high-quality RCTs are those that receive high scores in Design Quality (2.0 or higher) from both study reviewers; outcome evidence must also be consistent with the direction of the program’s overall rating.

7 Studies published after 2014 were also significantly more likely to use randomize control trials, which may account for their higher likelihood to be No Effects.

Themes Across the “Program Insights for Practitioners” Commentaries

In addition to each program receiving an overall rating, MENTOR’s Director of Research and Evaluation wrote a “Program Insights for Practitioners” document to capture program design and implementation considerations from the lens of an expert on the experiences of program developers. This section discusses patterns across these commentaries, which are referred to as “Insights documents.” Identifying themes that emerged across the Insights documents is valuable because the ratings discussed in the last section emphasize behavioral outcomes related to crime and justice system involvement, whereas the Insights documents emphasize processes that can provide takeaways for program developers. For more information about how the Insights documents were analyzed, please refer to the Methods box below.

|

Method Program Insights were examined by two of the report authors (A.G. and J.P) to identify themes (i.e., recurring or related takeaway points) across the different insights written for each program. Both analysts are NMRC Research Board members with expertise in youth-adult relationships and qualitative research; neither have any other affiliation with any of the reviewed studies or programs. A multi-step process was used for analysis. First, the two researchers divided the Program Insights documents equally between them. Each researcher then undertook an initial review of their assigned Insights, focused on familiarization of the data by program group (i.e., No Effects, Promising, Effective), with particular attention to facilitators and barriers to effectiveness. While reading their respective Insights, each researcher created a table with notes and interpretations, as well as a set of concepts reflected in the data (e.g., “Challenges to rigorous fidelity in evaluation and implementation” or “It is interesting in terms of youth characteristics, how this program failed in addressing significantly challenged youth, but the other addressed this with more intensive mentor training and support. Let’s look more into this.”). Overlap in interpretations were noted. This process generated an extensive set of key concepts. The two researchers then met to discuss these concepts. In doing so, they reviewed ways through which their interpretation was shared, as well as areas of discrepancy. In subsequent meetings and reviews of the Insights, the identified concepts were increasingly organized into iterative codes and clusters of meaning. Throughout the process, the two researchers consulted with the larger team, who were familiar with the profile information for each program and the process through which the Insights were developed, to clarify language regarding themes and discuss process and format for reporting of findings. At the conclusion of this process, the majority of the most salient concepts were grouped into themes. |

We identified five broad themes to capture processes occurring in programs discussed in the “Program Insights for Practitioners” documents:

- Ensuring Alignment Across Program Goals, Design, Implementation, and Evaluation

- Connections Between Mentoring Intervention and Mentees’ Home, Parents, and Larger Environment

- Engaging Others (i.e., peers, teachers, etc.) as a Web of Mentoring Support

- Tailoring Mentor Recruitment, Selection, Preparation, and Support to Effectively Serve Youth

- Optimizing the Role of Mentoring Within the Context of Programs with Multiple Components

Promising and Effective programs particularly exhibited these themes. When reflecting on the takeaways of each of these themes, it is important to consider the cost relative to impact of taking action on the themes. Although this issue in and of itself did not emerge as a key theme, it was raised at several points across the Insights documents reviewed. Thus, we see these themes as providing takeaways for program developers, rather than being prescriptive.

Below, we describe each theme in more detail, propose takeaways for program developers relevant to each theme, and provide illustrative examples of each theme, including direct quotes from the Insights documents. Theme 1 was the most prominent and multifaceted across the Insights documents. Themes 2-5 were smaller, standalone themes that extended the idea of intentionality between program elements raised in Theme 1.

Theme 1: Ensuring Alignment Across Program Goals, Design, Implementation, and Evaluation

The most prominent theme is the importance of ensuring that a program’s design, implementation, and evaluations are in alignment, both with each other and with the program’s ultimate goals as reflected in the broader aims of the program developers. As a whole, the Insights documents suggest that programs rated as Effective reflect intentionality of their development, with a deliberate focus on aligning core program practices with other program elements (e.g., program theory, mentor training, fidelity to program model, evaluation criteria). In contrast, this is an area of needed attention and growth in programs rated as No Effects.

A takeaway of this theme for program developers is to regularly ask: “Is there alignment between the program elements we are considering?” Indeed, aligning program elements with real world practice is key to effectiveness, and is also the most significant barrier to program fidelity. Our analyses of the Program Insights documents suggest the following are important questions for program developers to ensure alignment:

- Is the design of the program well-suited to achieving its intended outcomes? This could include developing a theory-based model that aligns with youth needs and with the local context, so there is a goodness-of-fit.

- Is the program being implemented in a manner consistent with this design “blueprint?” This might involve training program staff and mentors on program theory and expectations to strengthen fidelity to the program model. This may also include understanding what core elements need to be implemented with fidelity, and what elements can be adapted to fit with the local context to strengthen implementation quality.

- Are evaluation activities focused on the processes and outcomes of highest priority and relevance in the context of the program’s overall goals and strategies for achieving them? This might involve using evaluation activities to support continuous improvement.

In some instances, multi-faceted alignment is reflected by significant alignment between theory and program implementation, built on careful consideration of the characteristics of the youth served. Both My Life, a Promising program, and Better Futures, an Effective program, use self-determination theory to guide their program design because of the characteristics of the youth they serve. In the case of Better Futures, the Insights document argues that the program designers select self-determination theory to guide their mentoring efforts because the foster care youth they serve are youth “who by nature of their experience in the child welfare system may have felt disempowered in the course their life has taken.” As a result, “the program is built on a foundation of self-determination, and the idea that if these youth are put in the driver’s seat of their postsecondary planning, and provided with just enough mentoring, skill development, and instrumental support as scaffolding, the results will be meaningful.”

In other instances, multi-faceted alignment is reflected by coherence between program implementation and program theory to achieve fidelity. For example, the Better Futures program, referenced above, also maintains alignment with program goals by intentionally balancing rigidity and flexibility in their expectations of mentors. This ensures fidelity to program theory in a way that is replicable. The Insights document states, “Even though the program allows for a lot of flexibility, their fidelity results speak for themselves: 100% participation in the Summer Institute elements, 99.3% in exposure to the 11 self-determination skills, and 90.4% participation in the 17 experiential activities. These results speak to a program that allows mentors to give mentees the right developmental experiences, but also ensure that everyone in the program is getting a robust intervention.”

Quantum Opportunities, an Effective program serving 9th graders through high-school graduation, integrates “long-term mentoring into other services and supports and provides a depth of mentoring relationship that fits with the overall theory of change of the program.” In addition to clearly delineating the role of mentors, the program “even sought to determine the ideal number of hours that a student would participate in mentoring, tutoring, leadership training, and the other program activities over the course of a year.” This suggests that these components are carefully considered and monitored over time, demonstrating intentionality in incorporating mentoring alongside other youth development components toward program goals.

Our review suggested that aligning program elements with real world practice is key to effectiveness and is also the most significant barrier to program fidelity. As stated in the Insights document focused on the Check and Connect program, rated as No Effects: “One of the real conundrums mentoring programs face is how they can both build on and implement research-based ‘effective’ practices and program models, while also allowing for enough flexibility to customize an intervention or specific practice for local context or needs.” The Insights includes two evaluations of the Check and Connect program, both of which were implemented with fidelity and customized to different groups of youth. The effectiveness of the program varied, however, as the intended flexibility may have failed to capture some key elements of effectiveness across program schools and the Insight document argues that “sometimes rigidity of implementation may be the practitioner’s best friend.” Clearly, the tension between manualized, and measured, implementation and flexibility is ongoing, and highlights the complexity of developing alignment across these elements of Effective programs.

Another aspect of multi-faceted alignment involves aligning the expectations of the program with the expectations of the mentors. This coherence strengthens fidelity to the program model. In the case of the ambitious National Guard Youth ChalleNGe program, effectiveness was impacted by a lack of alignment between mentors’ program expectations and program implementation in terms of a lack of clarity regarding the mentor’s role. Per the Insights document, “a key takeaway for practitioners is that if mentors are to be used in supporting other intervention work, their role must be clearly defined and implemented with fidelity if it’s to be as effective as hoped.” It went on to state, “What results like this provide a program is the opportunity to strengthen their model. Mixed findings indicate that a program might be on the right path but could also take a fresh look at its theory of change and strengthen services in some key areas.” It is refreshing to see that the Insights document views the evaluation results as an opportunity to “strengthen their model” by increasing alignment between program implementation and mentor expectations.

Using continuous improvement to increase alignment was also alluded to when discussing how Quantum Opportunities reflected “thoughtful program replication.” The Insights points out that the Effective program “built on a much earlier iteration of the Quantum program.” This likely sets the stage for the Insights document to report that the program “put a lot of thought into the communities where this program might be a good fit, and the evaluation details the training and technical assistance provided to help with program implementation as these sites worked out the nuances of service delivery and modified small aspects of the model (such as the stipends) to meet local needs and circumstances. The result was cross-site results that looked remarkably similar, while also producing a wealth of information about how the program appeared to thrive best in each unique community.”

To be sure, as depicted by the Youth Advocate Program, rated as Promising, the question of implementation and dosage is complicated. As stated in that program Insight, “One of the most interesting aspects of the Youth Advocate Program (YAP) model is that it is fairly short-term compared to many community-based mentoring opportunities…at first this may seem surprising, given that YAP serves youth who are not just ‘involved’ in the juvenile justice system but who have violent or multiple serious offenses that have them facing incarceration in a juvenile detention facility. Well, what YAP lacks in duration, it more than makes up for in intensity.” The Insights document goes on to outline the YAP’s intensive and flexible model and incorporation of paid mentors, that ranges in weekly hours from 7.5-30, depending on mentee’s presenting need. Therefore, although it is short-term, it remains intentional in terms of fit and flexibility between mentee need and program delivery, and therefore demonstrates promise as assessed by these Insights.

As a whole, Effective programs reflect intentionality in their development, with a deliberate focus on aligning core program practices with program theory as described in Theme 1. Themes 2-5 below are described as smaller, standalone themes that extend the idea of intentionality between program domains, such as program goals (i.e., aims/model/theory), design (i.e., activities), implementation (i.e., accordance with design), reach (i.e., actual youth served), and/or evaluation (i.e., measures/results).

Theme 2: Connections Between Mentoring Intervention and Mentees’ Home, Parents, and Larger Environment

As an extension of Theme 1’s focus on intentionality in developing mentoring programs, other themes emerged in the data between the program and community resources (as outlined here and in Theme 3 that follows). Theme 2 underscored the importance of creating the type of connections between home, family, and the larger environment that could support the impact of mentoring.

A takeaway of this theme for program developers is to ask: “In what ways, if any, would building bridges between program content and the outside environment in which youth spend significant amounts of time support program goals?”

This theme is reflected frequently across program Insights, including programs that build connections with parents. For instance, Baloo and You, rated as Promising, connects mentors with parents to help facilitate future academic success. The Insights document discusses how Baloo and You intentionally engaged parents, stating: “mentors spend time with the parents and caregivers of mentees and, if the grades are coming around, really encourage them to have their child apply to the high track. This is likely something that many of these parents may have never even considered for their child. And into their life comes a college student who seems to be making a difference with their child and encouraging them to take the ‘path not taken.’” The Insights document argues that, based on Baloo and You, “mentoring programs may want to consider how mentors can not only influence the academic performance and self-efficacy of students, but also how they can influence the decision-making of parents, getting them to consider a new direction for their child’s education.”

Theme 3: Engaging Others (i.e., peers, teachers, etc.) as a Web of Mentoring Support

Connection to the community was also demonstrated in the third theme, which highlights the role of mentors within a network of relational support (e.g., connections with teachers, other supportive adults, peers) in bolstering the impact of mentoring programs.

A takeaway of this theme for program developers is to ask: “Are there other people in youth’s ecology beyond the mentor that could be leveraged to supplement mentoring? If so, who would be most valuable to leverage for the program’s focus?”

This could include encouraging mentors to leverage preexisting supportive relationships to increase their own support. In the case of Quantum Opportunities, rated as Effective, the Insights document highlights, “Mentors are expected to get to know the Associates family and friends and integrate themselves into the existing web of support in the student’s life and community.” In this example, the program builds in expectations that mentors build relationships with mentees’ family and friends as part of their role, thereby leveraging the strength of this system of relationships. In short, mentors are not alone in supporting youth, but join others in doing so, and perhaps leverage the strength of these relationships in increasing support to the young person.

Two Promising programs — School-Based Mentoring for At-Risk Middle School Youth and Home Visiting Program for Adolescent Mothers — support effectiveness by engaging an even wider range of people in the mentee’s ecology. In the school-based program, “teachers and other school staff served as mentors with encouraging results.” In the case of the Home Visiting program, although “strong volunteer mentors served as the face of the program and the main deliverers of the curriculum and intervention, they did not go into this alone.” Volunteer mentors are recruited from the communities of the adolescent parent mentees, and partner with social workers and other professionals to facilitate referrals and mental health monitoring. These and other Promising and Effective programs demonstrate the potential value of intentionally incorporating other supports, and in some cases, professionals, to accompany the work of mentors, and ultimately strengthen the mentee outcomes of interest to the programs.

Similarly, Fostering Healthy Futures, a Promising Program, is an example of mentoring in partnership with professionals. In this program clinicians offer separate but complementary support to young people. It provides youth in foster care with a “blend of one-to-one mentoring and more direct clinical support, in this case a series of manualized and clinician-led skill-building group activities over 30 weeks.” As clinicians lead group training sessions for young people in foster care, mentors support young people outside the groups. The Insights document reflects, “Having this kind of focused clinician-led skills group training in addition to mentoring allows for mentors to focus on, well, mentoring.” In other words, engaging clinicians allows mentors to do what they do best, which in this case involves supporting and enjoying the young people, while trusting that trained professionals can more directly address mental health and well-being.

Peers also provide important support in the web of mentoring, according to review of these Insights. For instance, the Sources of Strength model, rated as Promising, identifies peers in the students’ school ecology. This model then makes use of these peer leaders in advancing suicide prevention within the peer ecology. This program engages these “key peer leaders” as “both recipients and creators/deliverers of the program itself” to leverage the power of cliques to disseminate information important to suicide prevention. This innovation in the field expands the web of mentoring, while also illustrating alignment between very difficult and important program content (i.e., suicide risk and prevention) and youth access (i.e., through peer leaders as mentors), to create a Promising program.

Theme 4: Tailoring Mentor Recruitment, Selection, Preparation, and Support to Effectively Serve Youth

Programs rated as Effective and Promising recruited mentors and supported them to address specific youth needs. These programs carefully considered the role and task of mentors for their program, and tailor recruitment, selection, preparation, and the support of mentors to mirror these roles and tasks. Effective and Promising programs do not leave the mentoring relationship up to happenstance, and instead focus on the careful matching of mentors and youth based on relevant criteria.

A takeaway for program developers is to ask: “In the perfect world, what would the mentors in this program accomplish based on the program focus? What roles and tasks are most aligned with youth needs served by this program? What structures can be put it in place so the program can reach this ideal?”

In terms of recruitment and selection, some of the Insights documents discussed how programs targeting a specific population were deliberate in choosing mentors to serve specific types of populations. Better Futures, a program rated as Effective, provides a useful example of this. The Insights document argues a “key factor in the success of Better Futures may be who they ask to fill the mentor role. The mentors in this program are all young adults who have been to college and who also themselves have been in the foster care system or dealt with mental health issues.” My Life, a program rated as Promising, also provides a helpful example of this theme. My Life “placed greater emphasis on who was serving in the coach/mentor role, choosing to emphasize the recruitment of individuals who were slightly older than participating youth and who had been in foster care or wrestled with a disability themselves.”

Beyond recruiting mentors, programs rated as Promising or Effective tend to focus on supporting mentors in their intentional roles. In some cases, this support focuses on training. For instance, Great Life Mentoring, rated as Effective, tailored their training to their population (i.e., youth facing mental health challenges). The excerpt below highlights how Great Life Mentoring (GLM) prepares mentors in ways that align with the needs of the youth served, and also supports the mentors with monthly supervision:

- The Great Life training covers topics such as attachment theory, thus positioning mentors to be better prepared to offer corrective attachment experiences that allow youth to reframe their perceptions of closeness and belonging in relation to others. The training also covers topics such as self-awareness, emotional health, displaying empathy, and setting clear boundaries, all of which are regarded as important to working effectively with the youth who are served by this program. This robust training is supplemented by monthly in-person supervision by a GLM staff person for the first year of the match. Along with the usual purposes that would be served by this supervision in any program, in GLM it allows mentors to further learn about and act in support of the youth’s overall treatment plan and areas of emphasis for growth and change set out by the youth’s mental health providers.

In contrast, Arches, a credible messenger program that connects youth to mentors with similar life experiences and is rated No Effects, is described in the Insights document as largely missing their target because of lack of support for mentors. The Insights document made a point of stating that “the design of Arches seems tremendous on paper.” However, this “tremendous” design was not successful because Arches “faced challenges using less skilled mentors” such that it was “clear that credible messengers may need additional support to be so deeply responsible for delivering what can be a fairly technical and nuanced intervention like Arches.” We speculate that providing more support for the mentors would have better fulfilled the program design. This lack of alignment between program design and delivery of necessary support to mentors appears to hinder effectiveness. It should be noted that the tailoring of mentor support does not have to take the form of training. Alternatively, it can include having staff support mentors or provide materials that scaffold elements the program values in the mentoring relationship.

Theme 5: Optimizing the Role of Mentoring Within the Context of Programs with Multiple Components

Theme 5 focuses on when and how to optimize mentoring when considering different program components. This includes using different modes of connection to enhance mentoring relationships. It also includes delineating mentoring in a multicomponent program such that each component serves distinct but complementary roles or functions. This theme also serves as a reminder that too many components that do not align with program aims may dilute the impact of the mentoring component.

A takeaway for program developers is to ask: “How can the program optimally leverage the power of mentoring? If relevant, how does the program delineate the mentoring component in a multicomponent program?”

The Insights explores various ways that programs combine mentoring models to strengthen the modes of connections (i.e., virtual and in-person mentoring, developmental and instrumental approaches). As demonstrated through the Insights analyzed, integrating virtual and in-person components may strengthen programs’ capacity to achieve their desired outcomes. For example, when discussing the E-Mentoring Program for Secondary Students with Learning Disabilities, a program rated Promising, the Insights argues this point in relation to program goals, such that “programs that are intended to help a youth through a difficult transition should think about whether online communication could strengthen their program design or outcomes.” In some cases, advancements in social media and technology can shift how mentoring programs think about integrating on-line interactions with a more traditional, in-person program. As stated earlier, modifications should be intentionally administered in a way that aligns with program theory and prioritizes the needs of the youth the program is most focused on serving.

In the analysis, the combination of developmental and instrumental mentoring also emerged as a noteworthy program feature or characteristic, particularly in relation to Better Futures, a program rated as Effective. One of the main factors highlighted in the Insights document as contributing to the program’s effect sizes, which ranged “from .74 to 1.75 for just about every outcome the evaluation examined”, was that their mentoring relationships were “in many cases, highly ‘instrumental’…but the way that the program does this is also relationship-driven, and there is a heavy emphasis on personal growth, reflection, and peer support.” The program supports instrumental mentoring in a flexible way by providing mentors with a set of different experiences relevant to post-secondary transition (e.g., figuring out housing) that mentors could select as most relevant to their mentee. Alongside these offerings, Better Futures also attends to fostering personal relationships between young adult mentors and mentees.

Discussions of programs that were rated as having No Effects underscored how important it is for program developers to engage in careful reflection on how many components to include in a program. For instance, the Insights document argues that Chance UK was a well-designed program guided by mentoring research, but “may have had null effects because their target population and goal of behavioral change needed to complement mentoring with behavioral interventions.” On the other hand, the Insights document proposes that One Summer Plus, a program rated No Effects that provides mentees with employment opportunities, may not have seen differences on outcomes when adding an additional component of a staff-led SEL curriculum because the mentoring process could have been intentionally leveraged as a space for developing SEL skills, arguing:

By giving the young person a job or other challenges that will test them in new and unexpected ways, mentoring programs may provide valuable on-the-fly learning environments that, with the help of mentors, will allow youth to build SEL skills and apply them in the real-world. Mentors can guide and step in if the youth gets in over their head with a challenge, but there is something to be said about developing these skills organically in the real-world settings where they will need to be applied, rather than doing it in a separate, formal learning environment where skills are taught using a manualized curriculum in a vacuum.

Overall, these findings suggest a need for leveraging the power of mentoring optimally in and of itself, or in the context of other program components.

In the review of Insights, examples arose where programs included too many components that did not align in terms of program aims. At times multiple components may distract from the larger program aim and also dilute the impact of the mentoring component in program evaluation that leads to No Effects. In these cases, how can evaluation discern the impact of mentoring on its own? Pathways to Education, a program rated Promising, provides a helpful example of the difficulty of teasing out the role of mentoring in evaluation outcomes. As stated, “Clearly, Pathways youth are receiving mentoring, perhaps lots of it, but the details in how that works in synergy with the other program components still remains a bit of a mystery,” especially when “the mentoring that happens seems inadequately described in the study cited in the formal review.” In contrast, Insights underscore how delineating the mentoring component was clear in the design of Quantum Opportunities, a program rated Effective repeatedly referenced, because it “gives its mentors clear roles and responsibilities within the broader suite of supports.” In short, delineating the mentoring component in multicomponent programs is a challenging and critical process in evaluating practice.

Discussion

Programs reviewed varied greatly in their characteristics. The mentoring programs featured in this review (all of which are included in the MPG) served youth that were diverse in ethnicity, age, gender, and geographic location. While most programs took place in schools or community settings, there were also examples of mentoring in the home, on college campuses, and in the workplace, as well as some instances of e-mentoring. Mentoring mostly occurred one-to-one and was delivered by an adult, but about a third of programs included group mentoring, and about a fifth included peer mentoring.

Programs reviewed varied in their impact on youth outcomes. While the majority of programs received a rating of either Effective or Promising, about one third of the programs (37%) received a rating of No Effects. (As we discuss below, the CrimeSolutions rating system emphasizes justice-related outcomes. It is possible that the ratings for some programs may have been different had the rating system reflected other priorities.)

Our quantitative analyses showed significant associations between program effectiveness and prior research in support of the program, as well as two study characteristics, the use of a high quality RCT and date of study publication. Programs with a greater amount of past research in support of their design were more likely to be rated No Effects (p<.05). While this is an unexpected finding, it underscores the theme that designing a program in line with past research can be detrimental if it interferes with the program’s alignment with its own unique needs and resources. Furthermore, programs that were evaluated with high quality RCTs were more likely to be rated as having No Effects (p < .05), as were programs that were evaluated with studies published relatively recently. It should be noted, however, that the relationship between these study characteristics and effectiveness rating was far from perfect. In fact, some of the programs receiving the highest possible rating (Effective) were evaluated with the aid of RCTs or with studies published relatively recently.

The quantitative analyses also showed that, within the sample of programs included in the MPG, program characteristics (e.g., mentoring format, setting, demographic characteristics of mentees) were not related to program effectiveness. This finding is generally consistent with the results obtained in meta-analytic studies, including studies that have examined a broader range of mentoring programs than found in the MPG. With few exceptions, the meta-analytic studies tend to find that basic program characteristics, such as mentoring format, have little evident bearing on the potential for programs to have a desirable impact on youth outcomes (see DuBois et al., 2002; DuBois et al., 2011; Raposa et al., 2019).8 Likewise, these meta-analytic studies observe favorable effects across mentoring programs that vary widely in terms of the demographic characteristics of program participants. As a result, researchers have highlighted the flexibility and broad applicability of youth mentoring efforts. It appears that, generally speaking, effective youth mentoring can be delivered in a variety of populations and settings, and through a range of program types.

At the same time, the extant literature highlights the importance of certain other program features, especially the ability of programs to foster close, enduring, and developmentally enriching connections between mentors and mentees (Rhodes & DuBois, 2008). Stronger program effects have been associated with the adoption of a range of practices, including those that would be expected to enhance the quality and intensity of mentoring relationships, such as ongoing supervision, training, and support for mentors; parent support and involvement; structured activities designed to enhance mentoring relationships; and expectations that support frequent contact and long-lasting mentoring relationships (Rhodes & DuBois, 2008).

Our qualitative analysis of details retrieved from the Program Insights documents allowed for an examination of such program features. These analyses revealed common themes and suggested factors that may contribute to program efficacy, or lack thereof.

The strongest theme that emerged from details in the Program Insights was the intentional alignment between program goals and implementation, which led to stronger program effects. For programs rated as Promising or Effective, the Program Insights documents frequently referenced intentional alignment as an area of strength. For programs rated as No Effects, the lack of such alignment was frequently referenced as an area in need of further attention.

In general, programs that were rated Promising or Effective were noted for their strong and deliberate linkages between program theory/design; mentor roles, tasks, and expectations; the needs of the youth being served; and the youth outcomes to be prioritized. In such programs, for example, obvious care was taken to determine the best role for mentors, and mentor recruitment, selection, training, activities, and support were all tailored accordingly. Perhaps for this reason, Promising and Effective programs tended to avoid problems involving a lack of clarity regarding the mentor’s role—the very kind of problem noted among programs receiving a No Effects rating.

Programs rated as effective or promising were also noted for their deliberate leveraging of resources to strengthen mentoring relationships, thereby likely increasing the likelihood of positive youth outcomes. For example, such programs encouraged mentors to make connections with their mentees’ parents and friends and to enlist this larger “web of support” in the mentoring process. Likewise, some programs in this category partnered mentors with social workers or other professionals, allowing them to work together to monitor youth, address needs, and maximize positive outcomes. In the context of the more effective multicomponent programs, in which it was deemed necessary or desirable to supplement mentoring with additional services (e.g., tutoring, leadership training), care was taken to determine how to best incorporate mentoring alongside other program components. In short, the more effective programs included in the MPG were noted for the thought and attention they gave to the entire process of building, enhancing, and maintaining high quality mentoring relationships. This often resulted in clear, specific, and carefully considered plans and means for building, maintaining, and reinforcing impactful mentoring relationships—tailored to the unique context in which each program operated.

These findings provide implications for practice and research. Each are discussed below.

Practice Implications

The findings shared in this review do not point to a single template for effective programs. Rather, the themes and examples described earlier in this review suggest that, in effective and promising programs–which come in a variety of “shapes and sizes”–program leaders and staff give careful consideration to each aspect of the mentoring process in light of their particular program goals, the needs of the youth population being served, the resources available, and so forth. In such programs, they are intentional in their efforts to foster close, strategically-oriented, and impactful mentoring relationships.

We hope the themes and program examples described in this review will help program leaders and staff ask appropriate questions about their program elements (e.g., mentor recruitment and selection, training and support) and how to align them with the overarching program goals. For example, these themes and examples could help program leaders and staff identify considerations, decision points, and possible options for improving or maximizing the effectiveness of their own programs. (For additional training and technical assistance in this area, visit the website of the NMRC at https://www.mentoring.org/resource/national-mentoring-resource-center.)

We also recognize that programs must consider cost relative to impact as they make decisions about their program. While consideration of cost relative to impact did not emerge as a key theme, it was raised at several points across the Insights reviewed. Evaluating programs inclusive of cost allows us to intentionally consider the alignment of program elements toward program goals. It also equips programs to consider the effectiveness of program investments, particularly in light of limited resources, relative to various program goals, components, and outcomes. As needed, programs can pool resources and incorporate multiple disciplines to learn from one another. Lessons learned can in turn inform future program investments, with an eye toward the alignment addressed as the primary theme within the qualitative component of this analysis.

-

Reference 8 Certain meta-analytic studies find that program effect sizes are moderated by gender or by the risk profiles of youth, although such findings are inconsistent across studies (e.g., see DuBois et al., 2002; Raposa et al., 2019).

Research Implications

Our review suggests the importance of examining program mechanisms that relate to effective outcomes. Opportunities exist for more focused measurement and analyses in research on the “inner workings” of mentoring program effectiveness, the promise of which can be a more refined and “actionable” evidence-based foundation for informing practice as well as broader initiatives (e.g., funding opportunities).

To date, meta-analytic studies indicate that relatively strong effect sizes tend to be associated with programs that adopt a range of practices designed support and enhance mentoring relationships, such as setting clear expectations concerning the nature of the mentoring relationship, providing ongoing training and support for mentors, and involving parents in the mentoring process (DuBois et al., 2002; see also Rhodes & DuBois, 2008). The themes we identified through our qualitative review supplement, and are consistent with, this quantitative literature. Programs in the MPG that were rated as effective or promising tend to set clear expectations, provide ongoing training and support, and leverage support from parents and others in the youths’ wider social network (which, again, can give practitioners ideas applicable to their own programs).

Our findings also suggest areas for future research. First, it is noteworthy that the programs in our review varied greatly in the range of youth served, geographic locations, community settings, and format for mentoring. Areas ripe for greater “coverage” in future research include those in which there are relatively few studies, but evidence of promise for the programs that have been evaluated. These include, but not are limited to, programs designed specifically for male youth, those geared toward providing mentoring in rural locations, and programs that incorporate digital forms of communication between mentors and youth.

Second, from a methodological perspective it is noteworthy that only a small minority of programs have more than one independent study in their evidence base. Consequently, for all but a few programs, replicated findings of effectiveness (at least as represented in MPG and CrimeSolutions) are lacking. Multiple studies of a program’s effectiveness, furthermore, can be of great value for clarifying generalizability of results across different populations (e.g., racial/ethnic groups) or contexts (e.g., urban vs. rural).

Third, although a healthy proportion (about half) of the programs had been evaluated in a high quality RCT, which is generally regarded as the most rigorous design for assessing intervention effectiveness, our analyses further reveal that these programs are more likely to have received ratings of No Effects. This latter trend further underscores the importance of regarding existing ratings of programs as provisional and provides an impetus for more frequent use of RCTs for evaluating mentoring program effectiveness.

Fourth, in view of about a third of programs being rated No Effects and only a small portion being rated as Effective, a strong case can be made for research that takes programs through iterative cycles of data-driven strengthening in alignment with principles and strategies of the emerging area improvement science (Hudson, 2018).

Finally, for purposes of informing the evidence base for mentoring as a juvenile justice intervention strategy, it would be helpful to have increased assessment of justice-related outcomes in program evaluations, such as rates of offending and recidivism. These types of outcomes are examined in less than half of the programs that have been reviewed, but it would not be difficult to add relevant measures in future research. Evaluation of programs focused on youth with juvenile justice system involvement should be considered as a potential priority as well.

Limitations

It is important to highlight several limitations associated with our review. First, the programs included in the MPG may not be representative of the full universe of mentoring programs. Therefore, the extent to which the findings can be extrapolated beyond our particular sample remains unknown (although as described earlier, there is some consistency between our findings and those of meta-analytic studies that have examined a broader range of mentoring programs). Second, for many programs in our sample, program effectiveness ratings were typically based on the results of a single evaluation study. It is possible that the effectiveness rating for any such program could change as more (or more rigorous) evaluation studies become available. Similarly, the Program Insights documents reflect the observations of a single reviewer. As such, our findings and conclusions remain tentative. Third, it should be kept in mind that even programs rated as No Effects often had areas in which youth were indicated to have benefitted from participation. Related to this point, as would be expected, CrimeSolutions emphasizes effectiveness for addressing justice-related outcomes; although a fairly broad range of outcomes still have been considered (e.g., risk factors for delinquency), the possibility remains that ratings for some programs would have been different had the review system reflected other priorities (e.g., educational attainment). Fourth, our review did not account for certain program and study characteristics. These include intervention length and intensity as well as the duration over which outcomes were tracked following program completion (i.e., length of follow-up period). Each of these characteristics could be associated with program effectiveness and, ideally, could be examined in future reviews of the programs included in the MPG.

Concluding Thoughts

The limitations notwithstanding, we believe that our findings speak to the value of periodically taking stock of trends and patterns in the reviews of individual interventions that are the main focus of evidence-based program repositories such as MPG and CrimeSolutions. Furthermore, we believe that it is readily apparent from our analysis that commentaries such as the Program Insights prepared through the NMRC can offer detail and depth on potential implications for practice that complements the more descriptive and research-oriented content of traditional program profiles. When such commentaries are analyzed collectively, as in the present report, higher-order themes can be elucidated that extend beyond the context of an individual program and thus suggest broader principles for strengthening practice.

References9

DuBois, D. L., Holloway, B. E., Valentine, J. C., & Cooper, H. (2002), Effectiveness of mentoring programs for youth: A meta-analytic review. American Journal of Community Psychology, 30, 157-197. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014628810714

DuBois, D. L., Portillo, N., Rhodes, J. E., Silverthorn, N., & Valentine, J. C. (2011). How effective are mentoring programs for youth? A systematic assessment of the evidence. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 12(2), 57–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100611414806

Hudson, E. (2018, September 20). Six principles of improvement science. https://globalonlineacademy.org/insights/articles/six-principles-of-improvement-science-that-lead-to-lasting-change

Raposa, E. B., Rhodes, J., Stams, G. J. J. M. et al. (2019). The effects of youth mentoring programs: A meta-analysis of outcome studies. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 48, 423–443. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-00982-8

Rhodes, J. E., & DuBois, D. L. (2008). Mentoring relationships and programs for youth. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17(4), 254–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00585.x

9 Program evaluation references can be found under the “Evidence-Base (Studies Reviewed)” tab of the linked program profiles in Table 1a of the Appendix.